Gordon Brown was not the enthusiast for Afghanistan that his predecessor was, and had none of the passion that Tony Blair had for counternarcotics. With the Foreign Affairs Committee describing the partner nation role in counternarcotics as a “poisoned chalice” in 2009 the UK actively began looking for an amicable separation. With the election of David Cameron in mid 2010 – a prime minister who had no appetite for either Afghanistan or the drugs effort – the U.K. worked to secure a no fault divorce and extricate itself from a relationship that had become embarrassing.

Like some partners, the U.K. was beset with guilt, unable to just walk away from the relationship. It hoped to fill the gap with a suitable alternative – a partner that clearly wouldn’t be as intelligent, as charming or as good looking but would somehow suffice. Someone who would allow the UK to leave without acrimony and avoid the risk of it being accused of deserting its partner in their moment of need.

The UK was hoping that it would be the United Nations that would step in on the rebound. After all the United Nations Office on Drug and Crime (UNODC) in Vienna had always been somewhat jealous of the relationship the U.K. had found itself in with the Afghan government. So much so its Executive Director at the time, Antonio Maria Costa, would often brief against the UK to then President Karzai and others when the opportunity rose. From 2010 the UK began to position UNODC as a suitable alternative and look for the back door. There were of course doubts from both the Governments of the US and Afghanistan as to whether UNODC’s could be a responsible partner but nothing would deter the UK from packing its bags and leaving.

Leaving with Honour

However, it was important that when the UK did leave it would not be seen by others as wayward. Officials argued they had not been completely negligent as a partner and many of the problems lay with unreasonable expectations and an Afghan partner that was not fully committed to making the relationship work.

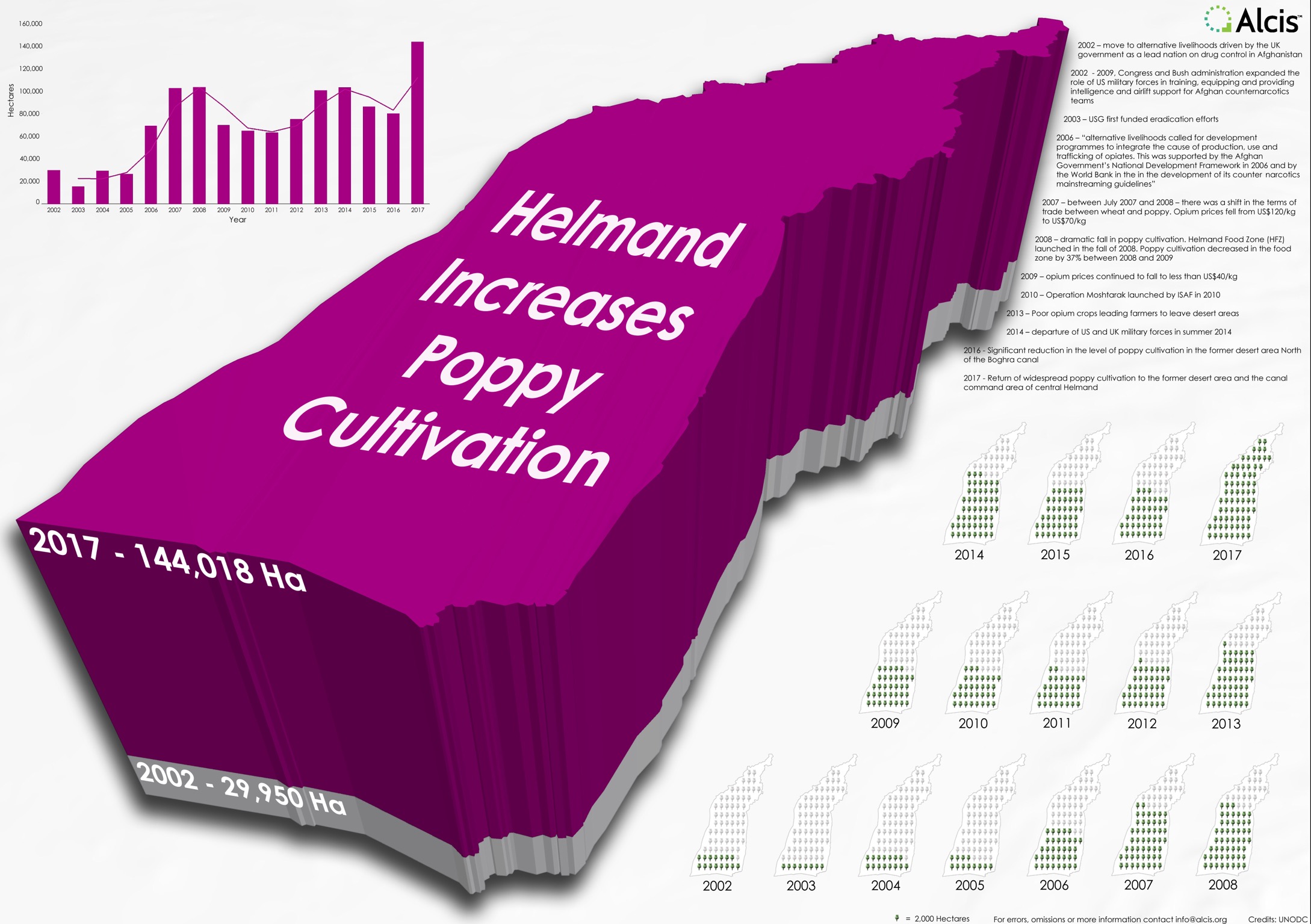

The UK also prided itself on the fact that poppy cultivation in the province of Helmand – where they had run the military and civilian effort since 2006 had fallen dramatically since 2008, from an estimated 103,590 hectares to 75,105 hectares in 2012. With this success British Officials reassured themselves that they were not deserting the Afghan government at all but had shown them that a more “comprehensive” counternarcotics effort under Afghan leadership could deliver results. Such was the purported success of the Helmand effort – the Food Zone- that the Afghan Ministry of Counternarcotics and the United States government even talked of replicating the approach in Helmand in 8 other provinces including neighbouring Kandahar.

Despite the metrics being in favour in Helmand the national figures were not so comforting for a partner determined to leave. By 2012 when the UK had all but completely abandoned its involvement in counternarcotics in Afghanistan and was barely on speaking terms with its former partner in the Afghan Ministry of counternarcotics, cultivation was at a new all time high of 154,000 hectares.

Hope over Substance

Forever the optimists UK officials consoled themselves with the fact that while things were far from ideal on the counternarcotics front they couldn’t get much worse. In fact, officials found some reassurance in the claim that with such high levels of cultivation things would only get better with the Afghan government in the lead and the UN on its arm.

At the time officials and analysts suggested that production in Afghanistan had reached a saturation point and supply was far outstripping demand. UNODC reported that annual production in Afghanistan had repeatedly exceeding the demand for opiates, often by as much as two fold. There was talk of inevitable market corrections and how the farmgate price of opium would fall deterring cultivation in future years. There was also reference to the expanse in cultivation in the former desert lands of Helmand, Farah and Kandahar. It was believed that the environmental constraints on production in terms of the availability of ground water, the problems of salination and falling opium yields was further evidence of an inevitable drop in opium poppy cultivation.

Alas, these hopes proved woefully misplaced. As early as 2013 opium poppy cultivation had risen to 209,000 hectares and by 2014 there was a further rise to 224,000 hectares.

Of course now UNODC has announced cultivation stands at a staggering 328,000 hectares in 2017; more than 100,000 hectares more than the previous high; over twice what it was in 2012 when the UK walked away from counternarcotics in Afghanistan; and more than four times the level of cultivation when the UK first took over its role as lead nation on counternarcotics in April 2002. How could things have gone so badly and how did so many get it so wrong when claiming things could not get any worse?

The first mistake in claiming market saturation was to assume that there is robust data on the demand for illicit opiates and therefore that there was oversupply. Estimates of worldwide opiate consumption have proven highly unreliable, dependent on governments reporting the scale of drug use within their territories. Many countries do not have robust data collection on drug use and have few incentives to reporting the scale of drug use amongst their population to the United Nations and the outside world.

The second mistake was to believe enough was understood about how the market for opium in Afghanistan worked. The fourfold increase in opium prices in 2010 following a 40 per cent loss in yield in the southern region revealed just how little was known about the farmgate trade in opium. In late 2008 UNODC had already tried to tie earlier increases in the farmgate price of opium despite the rise in production, to allegations of stockpiling and misplaced rumours about the possibility of a renewed Taliban ban. Most dismissed the claim that the Taliban would ban opium again as hearsay and were of the view that the insurgents had little to gain from such a move even if – and that was a very big if – they had the power to do so.

UNODC attributed the dramatic rise in prices in 2010 to low yields but previous cases of disease and failing crops had not had such a significant effect – particularly after what UNODC claimed to be repeated years of over production. At the time I speculated that the rise in price was more a function of the uncertainty created by the influx of significant numbers of US marines into Helmand – the surge – and what impact this was likely to have on production in key districts like Marjah and Nad e Ali, as well as traders ability to purchase, sell and process opiates. But this was based on fieldwork in central Helmand during the harvest season that year and a lot of conjecture on my behalf.

The third error in thinking that cultivation would fall after reaching the lofty peak of 154,000 hectares in 2012 was to assume that the rational response to falling opium prices was for farmers to reduce the amount of opium they cultivate. This may be the case for households who can produce other agricultural crops to sell or have viable wage labour opportunities. Under these circumstances it would make sense for them to reallocate their labour, land and water away from opium poppy. But in the absence of these opportunities why not continue to cultivate opium poppy? After all household labour has no monetary value if there is nothing better for it to do, and as long as there is a level of food production that can support the family, why grow a surplus of crops that have to be transported to market to sell, sometimes at a loss. Opium production is less price responsive than theory might suggest: with what is essentially free labour and with nothing better to grow on the land it makes sense to continue to cultivate poppy. At least opium can be harvested, stored and then sold when prices increase once again.

Moreover, farmers in Afghanistan, particularly those in the south west have proven adept at finding ways to reduce input costs. From the application of herbicides and pesticides to recent investments in solar-powered tubewells farmers have used improved technology to manage falling yields and falling farmgate prices to maintain and then subsequently increase opium production.

This leads us to the last and most fatal error in assuming saturation point had been reached in 2012 – and that was failing to see how the UK’s Counternarcotics efforts in Helmand was likely to play out in the medium to long term.

Far from building a replicable model the U.K.’s counternarcotics efforts set in play a series of socio-economic and political factors that helped change the physical geography of Helmand, so much so that cultivation rose from 75,000 hectares in 2012 to 144,000 in 2017.

The ban on opium and the provision of wheat seed and fertiliser undertaken under the auspices of the Food Zone program dispossessed sharecropping and tenant farmers of the land that they had grown poppy on in the central canal command area.

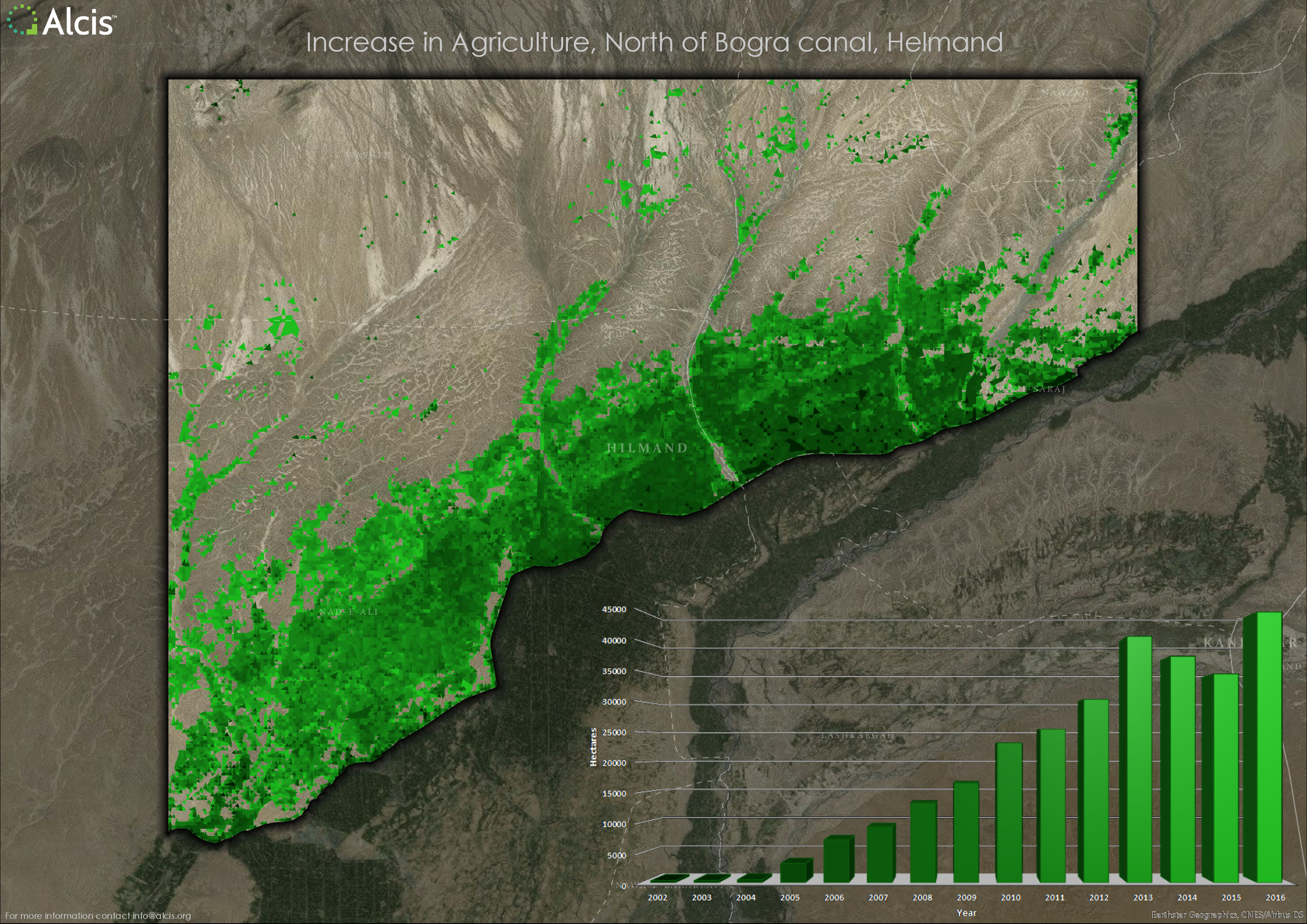

Without land and alternative sources of income in the fertile canal command area these families were driven into the former desert areas of the area north of the Boghra canal where they could grow opium beyond the reach of the Afghan government and NATO forces. Here they provided cheap and skilled labour to those that had already captured or purchased the desert land and supported its transformation from rocky barren soil into a swathe of opium and wheat. In time some of these new migrants accrued enough money to buy their own patch of land, sink a well, build a home and grow their own opium crop.

By 2017 there were 52,000 hectares of agricultural land in the area just north of the Boghra canal where 10 years before hardly anyone lived. Over 50 per cent of this land was poppy, grown by settled communities, many of whom now own land for the first time in their lifetime and who have no intention of leaving the area.

As the poppy has increased in the former desert lands it has also returned en masse to the areas of central Helmand where it was once successfully banned. In fact in 2017 opium poppy could be found across the canal irrigated areas even in areas like Bolan and Qala Bost on the outskirts of the city of Lashkar Gah where the crop had not been grown since 2008. The collapse of the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces and the loss of territory to anti government elements has been fuelled by the antipathy that the rural population feels towards a government that banned poppy and left them with no alternative. Far from offering a replicable model for drug control the Helmand Food Zone has increased the provinces capacity to produce more opium than ever before.

Regrets

One has to wonder given the poor judgement that informed the UK’s assessment of what would happen to the opium crop in Afghanistan once it left, how it views its former partner today. Does it feel guilt that its former partner, the Afghan government, not only failed to prosper in its new relationship with the UN, but that this union was undermined before it even began by the U.K.’s efforts in Helmand? Or does it see the meteoric rise in cultivation as vindication and is just grateful that it ended the relationship before things got worse – so much worse?

David Mansfield is a Senior Fellow at the London School of Economics. He has been conducting research on rural livelihoods and poppy cultivation in Afghanistan for twenty consecutive growing seasons. He has a PhD in development studies from the School of Oriental and African Studies, London and is the author of “A State Built on Sand: How opium undermined Afghanistan”. David has worked for the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit since 2005.