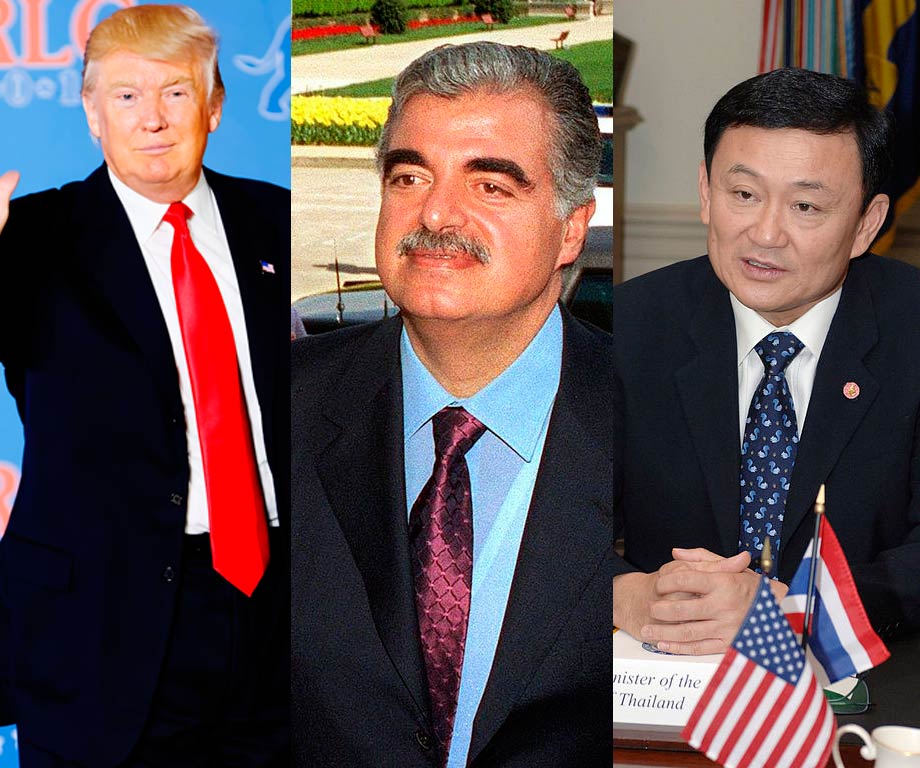

When the Cold War ended neoliberalism triumphed. Deregulation and privatisation buoyed new business empires in real estate, media, finance and telecommunications. After seizing economic opportunities, many of these new business emperors also sought political opportunities. Italian media mogul Silvio Berlusconi, Lebanese contractor Rafiq Hariri, and Thai telecommunications giant Thaksin Shinawatra became prime ministers in the 1990s and 2000s.

These individuals are prominent examples of the new tycoon-politics. They describe themselves as ‘self-made men’ but their rise had much to do with being in the right place at the right time during deregulation or an oil boom. Trump’s background is similar. He multiplied his father’s wealth through property deals in Reagan-era New York. Debt-fuelled expansion nearly pushed him into bankruptcy in the 1990s. Since 2004 he has concentrated on TV shows and product licensing.

Tycoons run as insurgents against faltering political systems and old economic oligarchies. The implosion of Italy’s ruling Christian Democrat party in the early 1990s ‘Clean Hands’ anti-corruption campaign opened the gates for Berlusconi. Lebanon’s civil war cleared the way for Hariri. Thaksin entered politics in the wake of the 1997 Asian financial crisis. The aftershocks of the 2008 financial crisis played a similar role for Trump. He channelled the discontent of America’s white middle class outside the major coastal metropolitan areas by mixing economic nationalism with xenophobia, racism, sexism, and Islamophobia.

Tycoons offer politics-as-business as an alternative to politics-as-usual. They run family businesses where top-down decisions are taken in a tight-knit circle of advisors. Berlusconi put a school friend at the head of his media holding company while Hariri made a school friend head of one of his banks and later finance minister. They both relied on former employees or associates to fill positions of state. Trump has also filled key government posts with people who stayed loyal even when his campaign foundered, and his son-in-law Jared Kushner has the role of senior advisor. Yet tycoons’ background in business does not equip them to deal either with the bureaucratic Leviathan that is the modern state, or with the give-and-take of democratic politics.

Conflicts of interest

Conflicts of interest abound with tycoon-politicians. Rafiq Hariri was a major shareholder of the development company that was reconstructing central Beirut and Berlusconi prevented regulation of his media conglomerate. Trump has handed control of his business empire to his children who were also part of the transition team which picked top officials. Berlusconi spent much of his energy as prime minister fighting ‘communist judges’ who were bringing charges against his businesses. Trump is set to have a similarly testy relationship with the judiciary, having accused a judge presiding over one of the astonishing 3,500 lawsuits he has been involved in of bias due to his Mexican heritage.

The highly personal style of ruling extends to international relations. Some tycoons rely on foreign backing on their way to power. Rafiq Hariri had been a Saudi envoy during Lebanon’s civil war and grew rich on royal contracts. While Trump may not be similarly beholden to outside powers, US intelligence agencies have pointed to Russia as the likely culprit in an e-mail theft from the Democratic National Congress, which benefited Trump when it was published on Wikileaks. America’s NATO allies have noted the billionaire’s embrace of Vladimir Putin with great alarm. Berlusconi had a similarly cosy relationship with Putin.

Tycoons can still have some policy successes. Hariri rebuilt central Beirut, albeit as a ghost town. Thaksin’s low cost healthcare provision was so popular that the coup plotters who deposed him in 2006 kept the policy. However, tycoons cannot meet the overblown expectations they raise in their election campaigns. The economic record of a Berlusconi or a Hariri was lacklustre at best. Trump’s promise to boost GDP growth to 4 per cent a year is unlikely to be met.

Few tycoons just fade away, some establish dynasties. After Rafiq Hariri’s assassination in 2005 the mantle passed to his son Saad. Following the 2006 coup that ousted Thaksin, his sister Yingluck fought her way back to the post of prime minister in 2011. What is most troubling about the Thai and Lebanese episodes are the tycoons’ divisive legacies. Saad Hariri led the ‘March 14’ coalition against ‘March 8’ around Hizballah. The two parties brought Lebanon to the brink of civil war. Post-coup politics in Thailand saw popular mobilisation and violence between ‘red shirts’ supporting Thaksin and ‘yellow shirts’ opposing him.

Trump may turn out to be the most dangerous tycoon yet, and not only because the USA are so powerful. Saad Hariri and Thaksin Shinawatra used divisive popular mobilisation only after they had come under violent attack through an assassination and a coup respectively. What sets Trump apart from the other billionaire politicians is that divisive race and gender politics are at the very heart of his project.

Hannes Baumann is a lecturer at the University of Liverpool. His current research looks at the politics of Gulf investment in non-oil Arab states. He is the author of Citizen Hariri: Lebanon’s Neoliberal Reconstruction, published by Hurst in January 2017.

This article was first published on 29 December 2016 by openDemocracy and is reproduced here with permission.