Pandemic, it seems, is not a word to be used lightly.

For several weeks now, the novel coronavirus outbreak that began in Wuhan in December has been spreading steadily from person-to-person and from country to country. At time of writing, China has recorded more than 40,000 infections and 908 deaths, surpassing the total set by SARS (also a coronavirus) in 2003, and outbreaks have also been reported on every continent and region of the world, with the exception of South America and Africa.

True, there have been fewer than 400 confirmed cases outside of China, suggesting that so far, checks at airports and border crossings are working. But with reports of human-to-human transmission in France, Britain and Germany, and multiple cases on a cruise ship moored off Japan, there is growing frustration at the World Health Organization’s refusal to use the p-word.

As one medical demographer tweeted this week: ‘We spend all this time preparing for the “next pandemic” and then when it arrives we split hairs over whether it’s a pandemic or an outbreak… FFS, it’s a pandemic.’

So why is the WHO so reluctant to call 2019-nCoV—to give the virus its official name—a pandemic virus? And what difference does their word choice make?

‘Pandemic’ has long been an imprecise and malleable concept. The term derives from the Greek word pan meaning ‘all’ and demos meaning ‘the people’. ‘Epidemic’ by contrast comes from the Greek word epi meaning ‘on’ the people.

The earliest usage in the English language comes in a 1666 book by the English physician Gideon Harvey in which he uses the term ‘Pandemick’ to refer to a malignant disease which ‘do generally…haunt a Country.’ Interestingly, though Harvey was writing just a year after the Great Plague of London, the reference comes in a tract about consumption (pulmonary tuberculosis), which was then very widespread in England.

Digital databases such as Google’s N-gram viewer reveal very few references to the term before the mid-nineteenth century. This all changed, however, with the spread of bubonic plague from southern China to Hong Kong and India—what became known as the Third Plague Pandemic—and the ‘Russian influenza’ pandemic that erupted in St Petersburg in December 1889. Coinciding with the growth of rail and steam ship travel, faster telegraphic communications, and the expansion of mass market newspapers, these pandemics were the first to be mapped—and reported—in real time.

Indeed, competition between foreign correspondents in St Petersburg, Berlin and other badly affected European capitals to be first with the news ensured that ‘dread’ of the Russian flu spread faster than the virus itself. Just as significantly, the Russian flu was the first time the wave-like nature of influenza and its association with ‘excess’ deaths due to respiratory disease had been studied in any detail. In particular, medical experts observed that the pandemic spread worldwide in three distinct waves; with the second wave in the spring of 1891 being more severe than the first, and the third wave in the winter of 1891-2 being more severe than either. In Britain alone more than 125,000 people perished in the pandemic—the majority from bronchitis and pneumonia. Worldwide, the death toll was in excess of one million.

The result was that whereas prior to 1890 The Times had used the term ‘pandemic’ just twice (and more or less as a synonym for an epidemic), after 1890 it became increasingly linked to the increasing speed of global communications and other tropes of modernity.

However, the event which perhaps did most to cement the pandemic in the public imaginary was the 1918-1919 Spanish flu. In a brief 11-month period, the flu—which most likely originated in the southern United States or northern France—spread to every continent and country on the globe, killing in excess of 50 million people. Only American Samoa, St. Helena, and a handful of islands in the South Atlantic escaped. It was truly a shared global disaster.

Since then, of course, we have had two further flu pandemics: the 1957 ‘Asian flu’ pandemic and the 1968 pandemic of ‘Hong Kong’ flu, each of which killed approximately one million people globally. Then in June 2009 the WHO officially designated the H1N1 swine flu outbreak, which had begun in Mexico two months earlier, a pandemic—even though the new virus went on to kill fewer people than die every year in a normal flu season.

The subsequent controversy (the swine flu was dubbed a ‘false pandemic’ and ‘the pandemic that never was’) reveals that ‘pandemic’ is as much a political and technical term as a medical one, its principal purpose being to bolster weak health systems and to unlock funds for diagnostic tests, and new drugs and vaccines.

Under the WHO’s phased pandemic alert system, the H1N1 swine flu met all the criteria for a pandemic: it was a new virus against which no one had immunity, and sustained human-to-human spread had been documented in at least two WHO regions. Just months before the WHO’s pandemic declaration in June 2009, however, the organisation had deleted a requirement that a new pandemic virus should also cause ‘enormous numbers of deaths and illness’. It was the absence of this severity test that led critics to question the WHO’s motivations and suspect its scientific advisors of being in the pay of Big Pharma.

‘the coronavirus epidemic already meets the WHO’s most basic definition of a pandemic’

One reason for the WHO’s reticence this time round is that it is wary of making the same mistake again. Besides, following its announcement on 30 January that the coronavirus outbreak constitutes a public health emergency of international concern, donors have promised additional funds and technical assistance, albeit not as much as WHO director-general Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, would like (last week he appealed for $675 million to fund a global response plan for the coronavirus; so far, the Gates Foundation has pledged $100m, the Wellcome foundation £10 million, and the UK $20 million).

Whether raising the alert to the pandemic level would unlock additional funding is unclear. The danger, of course, is that the opposite might happen and that it could spook financial markets and spark further restrictions on the movements of Chinese nationals and business travellers. Moreover, despite the deepening concern about the mounting cases and deaths in China, we are yet to see ‘sustained’ human-to-human spread outside of China—a key technical requirement for the WHO to raise the global alert to phase 4, much less phase six (‘widespread human infection’).

On the other hand, the coronavirus epidemic already meets the WHO’s most basic definition of a pandemic—namely, ‘a worldwide outbreak of a new disease’—hence the frustration of the medical demographer quoted at the outset.

On the day when the UK health secretary Matt Hancock has declared the coronavirus outbreak ‘a serious and imminent threat to public health’, I share these frustrations. As my latest book demonstrates, pandemics have always been in the eye of the beholder. For instance, in 1930 newspapers labelled the worldwide outbreaks of ‘parrot fever’ a pandemic—even though there was little evidence of human-to-human transmission, just 12 countries were affected and only 120 people died. Yet SARS, which killed nearly eight times as many and spread to 26 countries, was simply a worldwide epidemic.

Perhaps we should leave the last word to the late American virologist Ed Kilbourne who, noting a similar reluctance among his colleagues to designate some influenza outbreaks pandemics, quipped that pandemics were a little like pornography: ‘We all “know it when we see it,” but the boundaries are a little blurred.’

The Pandemic Century: One Hundred Years of Panic, Hysteria and Hubris

Hardback | April 2019 | £20.00 | 9781787381216 | 392pp

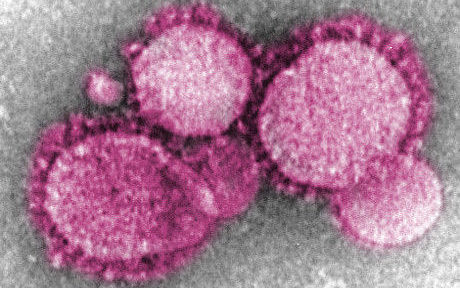

Featured blog page image: “Novel Coronavirus nCoV” by AJC1 is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Mark Honigsbaum is a medical historian, journalist, and author of, amongst other books, The Fever Trail: In Search of the Cure for Malaria and Living with Enza: The Forgotten Story of Britain and the Great Flu Pandemic of 1918. He is currently a lecturer at City, University of London.