Excerpt from Chapter 10 of An African in Imperial London: The Indomitable Life of A.B.C. Merriman-Labor

In the middle of August 1918, the H.M.S. Mantua was only two days into its familiar route from the Royal Navy Base in Devonport, England, to Sierra Leone when influenza broke out on board. By the time the vessel arrived in Freetown on August 15th, more than 200 of its crew were sick. [1] The Mantua’s captain sent a private note to Sierra Leone Colonial Governor Richard Wilkinson indicating that he would be unable to attend his Honor that evening at Government House due to illness on board.

It so happened that Wilkinson was entertaining a substantial naval party, including a Brazilian Admiral, a British Rear-Admiral, and several captains. When he mentioned the influenza aboard the Mantua to his guests they offered ‘the most positive assurances that no communication whatsoever was being permitted between the Mantua and the shore.’ [2] Convinced all was being handled appropriately, Wilkinson thought no more of it. The following day Freetown colliers sailed out to the Mantua and, as usual, loaded coal into its hold. Ten days later, 500 of the 600 of the men working in the Freetown coal yard were too sick to come to work. [3] The ‘Spanish Flu’ had arrived in Africa.

Influenza had swept the globe earlier in the year, but as it was generally mild it had caused little concern. But at the end of summer, a mutation transformed the mundane virus into a lethal disease, and the massive transport of people around the world in service of the European War spread it rapidly. In late August 1918, the flu epidemic erupted simultaneously in three places: Boston, Massachusetts; Brest, France; and Freetown, Sierra Leone.

The disease cut its deadly swath through Freetown, the Sierra Leone Weekly News reported, beginning ‘from the Government Wharf straight on to Kissy Road, Fourah Bay Road and Foulah Town.’ [4] Hundreds of people who had become suddenly ill swarmed to the Colonial Hospital. They had no idea how to deal with the distressing symptoms—high fever, bleeding from the nose and ears, excruciating headaches focused behind the eyes, nausea, vomiting, pain in the back and limbs, and delirium. Some were so ill they collapsed in the streets. One person described waiting for hours with three hundred other sick people at the Colonial Hospital. Another recalled that he was admitted but didn’t see a doctor for four days because many of the medical staff were desperately sick themselves. [5]

“With no clear explanation why the disease was so virulent, one West End doctor laid the blame on women’s fashions.”

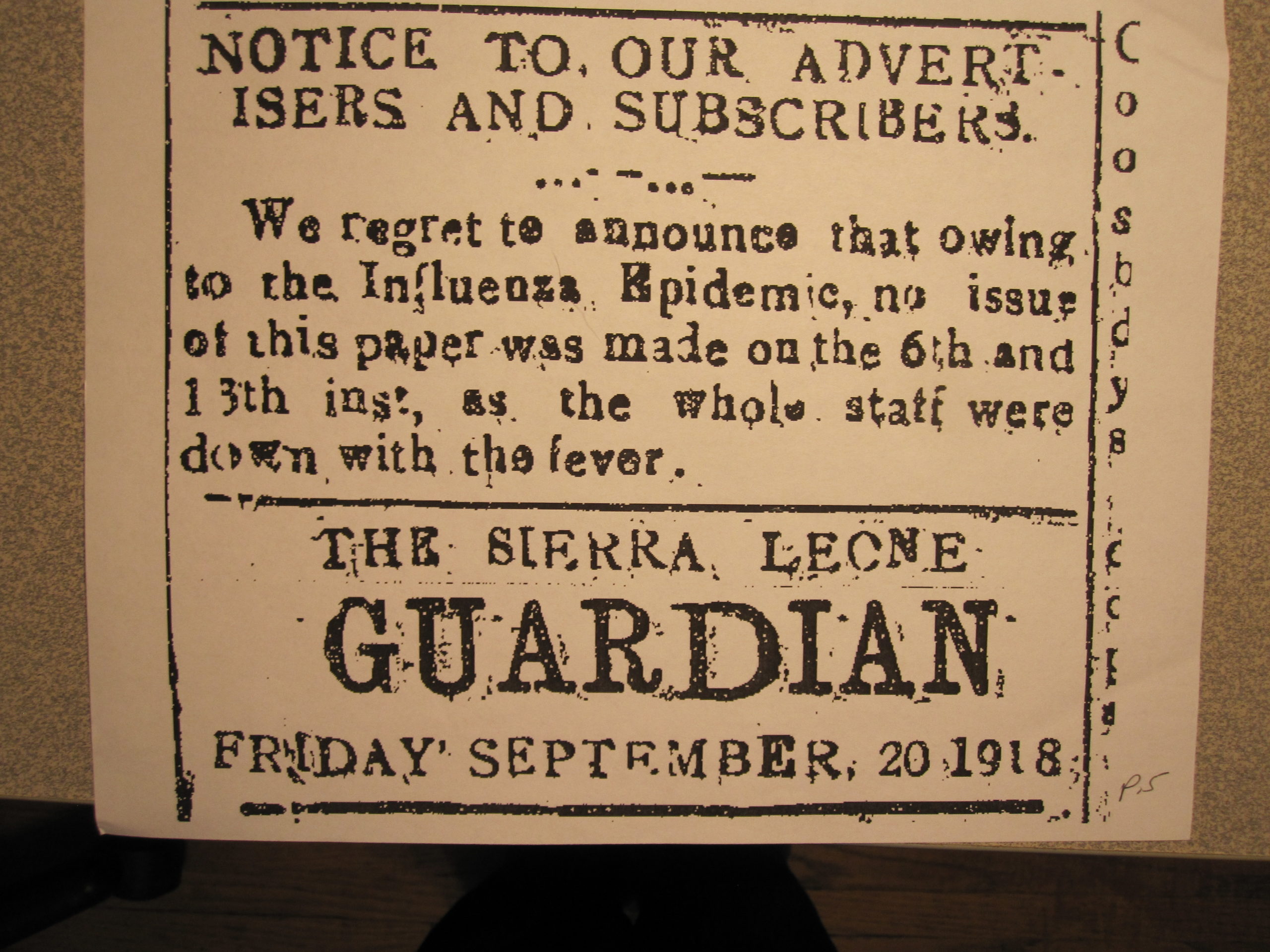

Business in Freetown ground to a halt. Shops were closed, train service suspended, churches emptied, the main thoroughfares deserted. The death rate soared: hundreds died each week. The dead came, the Sierra Leone Weekly News reported ‘from all classes and conditions—white and black; Agents of European Firms and Native clerks of Government offices, and mercantile establishments; unmarried young men and women as well as married.’ [6] The disease carried away the vulnerable—infants and the elderly—but was especially dangerous for those in the prime of life.

[…]

By late October 1918, the deadly strain of the flu had invaded London. ‘Influenza is spreading to an alarming extent,’ reported the Daily Mirror. ‘The virulent disease is seizing victims wholesale and the doctors in London are unable to cope with the stream of patients.’ [7] People who seemed perfectly well one moment, it reported would be deathly ill an hour later. As it spread, crowds lined up outside of hospitals, doctors’ offices, and pharmacies that didn’t have enough staff to serve them.It seriously disrupted the bustling city. Hundreds of policemen and firemen were too ill to work. So many drivers were down with the flu that buses, trams, and trains were placed on limited schedules. Places of business struggled on with skeleton crews. Because more than a thousand operators were sick, the Postmaster General asked Londoners to limit phone calls. [8] Even milk and bread were in short supply, according to the Daily Express. In some places, the paper declared, one needed a doctor’s certificate to get a pint of milk. [9]

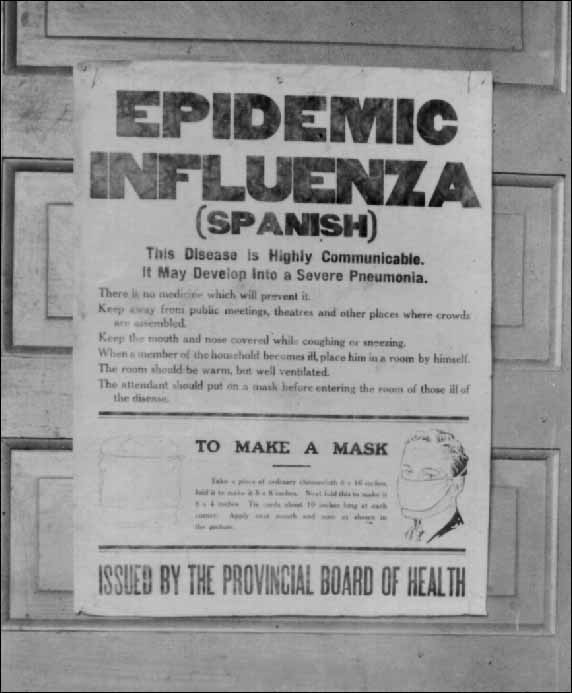

As in Freetown, doctors recommended bed rest, gargling morning and evening with an antiseptic mixture, and getting as much fresh air as possible. As panic rose with the death rate, medical officers assured people that ‘prompt and proper treatment would avert fatal developments.’ [10] When conventional medical treatment didn’t work, desperate Londoners also sought out alternative remedies. The list of products that claimed to prevent or cure influenza was mind boggling. Alleged remedies included aspirin, opium, quinine, cinnamon, ammonia, camphor, creosote, salt water, beef tea, cocoa, snuff, and alcohol. [11] ‘One must smoke, say some,’ the Daily Mirror reported, ‘others, however, say “Smoking is no use.”‘ [12] With no clear explanation why the disease was so virulent, one West End doctor laid the blame on women’s fashions. ‘Thousands of women victims of the epidemic owe their serious illness,’ he claimed, ‘to the wearing of low-necked thin blouses.’ [13]

According to one sardonic columnist, some people saw contracting the flu as a badge of honor. ‘We know that nothing can make you feel more virtuous than to appear at the office, at your war work, in tubes, omnibuses, and public places “believing” that you “have a touch of the ‘flu,”‘ wrote W.M. for the Daily Mirror. These ‘patients, victims, and culprits,’ he claimed, were quite proud of it. ‘Everywhere they talk so of the ‘flu and of their pride in spreading it about.’ The only thing to be done with them, he mockingly concluded, was punishment ‘with penal servitude, or bed.’ [14]

As in Freetown, undertakers were overwhelmed with the bodies and could not keep up with the demand for coffins or graves. One survivor remembered attending his father’s funeral in a church overflowing with mourners, and coffins stacked ‘one on top of the other’ at the altar. [15] According to the British Undertakers’ Association, during the period from late October to early November 1918, the death rate was higher than it had been for nearly 100 years. For the first time since Britain had begun keeping records, the number of deaths exceeded the number of births. [16]

An African in Imperial London: The Indomitable Life of A. B. C. Merriman-Labor | Hardback | June 2018 | £25.00 | 9781849049603 | 320pp

[1] Sheldon F. Dudley, “The Biology of Epidemic Influenza, illustrated by Naval Experience,”Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, (War Section) 14, no. 37 (1920-21): 45

[2] Governor Wilkinson’s report, TNA, Kew, CO 267/587, Influenza Epidemic, Sierra Leone Report 53257, 3.

[3] Governor Wilkinson’s report, TNA, Kew, CO 267/587, Influenza Epidemic, Sierra Leone Report 53257, 5.

[4] “The Health of Freetown, Sierra Leone Weekly News, August 31, 1918, 11.

[5] “Medical Department and the Influenza Epidemic,” The Colonial and Provincial Reporter, September 28, 1918, 5. W.F. Campbell, Medical Officer Report, TNA, Kew, CO 267/587, Influenza Epidemic, Sierra Leone Report 53257, 4.

[6] “The Health of Freetown, no. 2,” Serra Leone Weekly News, September 7, 1918, 8.

[7] “’Flu’ Grips Town and Country,” Daily Mirror, October 23, 1918, 2.

[8] “Flu Fright,” Daily Express, October 28,1918, 1.

[9] “Go to Bed and Stay There,” Daily Express, October 23, 1918, 3.

[10] “Flu Fright,” Daily Express, October 28, 1918, 1.

[11] Naill Johnson, Britain and the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic(New York: Routledge; 2006) 165.

[12] “What to Do With our Influenza Heroes,”Daily Mirror, October 24, 1918, 6.

[13] “More Doctors to Fight influenza,”Daily Mirror, October 30, 1918, 2.

[14]“What to do with Influenza Heroes,” Daily Mirror, October 24, 1918, 6.

[15] March Honigsbaum, Living with Enza: The Forgotten Story of Britain and the Great Flu Pandemic of 1918 (London: Macmillan, 2009), 132

[16] Andrea Tanner, “The Spanish Lady Comes to London: The Influenza Pandemic 1918-1919,” The London Journal 27 no. 2 (October 2002): 54.

Danell Jones is a writer and scholar with a PhD in literature from Columbia University. She is the author of The Virginia Woolf Writers Workshop; the poetry collection Desert Elegy; and An African in Imperial London (also available from Hurst Publishers), which won the High Plains Book Award for Nonfiction.