Lipika Pelham talks to Israelis and Palestinians about the divisive impact of war on mixed communities. As seen in Perspective.

Families of hostages protest on Kaplan Street, Tel Aviv

The first thing the children want to show me is the mamad. The safe room. A reinforced space mandatory in all buildings in Israel constructed after the Gulf War of 1991. My friend’s nine-year old son, Adam, asks if I know how long it takes for debris to fall on you after a rocket is intercepted by Iron Dome “missile repellent” – a term he uses.

When I don’t answer, he says: “Ten minutes”.

“Really?”

“Yes. It takes that long for the rocket to shatter and for the pieces to fall down. So you should take cover when you hear the sirens and stay in the security room for at least ten minutes.”

The room at the back of the ground-floor flat has a thick metal door that doesn’t lock from inside – because mamads are designed only to repel rocket attacks, not intruders. Which is why on the 7 October Hamas attack on southern Israel, the safe rooms failed to protect the people of the kibbutzim who took shelter there.

Feeling unsafe is the overwhelming national trauma

Adam shows me the spot where my mattress will be – in between his and his sister’s beds. So we’ll be safe from the falling shrapnel of a failed rocket. His thirteen-year-old older sister, Romi, helps me download the Israel Home Front alert app.

This is the first time these children have lived in an active war zone, where the sirens go off several times a day, and they need to run to the nearest bomb shelter or “duck under a bus” if they happen to be out. They have a fairly good idea of the parties engaged in this conflict. Romi pulls out a drawing where she has put Gaza and Tel Aviv at opposite ends, with their house with its mamad, in Jaffa, under an Iron Dome shield, and Gaza and its residents without safe rooms, exposed to rockets launched from Tel Aviv.

“Hamas sent hundreds of rockets last week, we destroyed nearly all of them. We sent some too, and more annoying ones that hit targets and kill thousands,” says Romi. Her drawing shows little Gazans running across the Strip looking for cover, but there is none.

The streets of Jaffa and Tel Aviv are empty. Two Saturdays since the 7 October massacre, the whole country seems to be lying in wait to feel safe again.

“This is the one time Israelis felt what it is like to be unprotected in half a century since the Yom Kippur War,” says the children’s mother, Yael Berda. She adds that feeling unsafe is the overwhelming national trauma at the moment. Yael teaches sociology at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. She is a prominent activist for Palestinian rights and one of the leaders of the movement A Land for All/Eretz LeKulam/Bilad Lil Jamiaa.

In October 1973, an Arab army led by Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on Israel as the country briefly let down its guard during the holy day of Yom Kippur. On 7 October 2023, some 1,500 Hamas gunmen broke through the boundary fence between Gaza and southern Israel and overran nearly 30 kibbutzim, killing 1,400 Israelis.

“The most difficult for me was the hours that it took for help to arrive,” says Yael. “It’s one thing to be attacked, and another to wait for six to seven hours for no help to arrive. That’s the crisis we’re in, that depicts the feeling of abandonment, the feeling of the decimation of the state.”

That latter phrase is repeated by Muhammad Fadila, a civil engineer and a native of Jaffa. We meet in a café where his best friend, Ziv, worked. Ziv was killed in the 7 October massacre. Muhammad says that the Palestinians inside Israel, known as 1948 Palestinians, or Israeli Arabs, have been facing state-sponsored “decimation” all their lives. He calls the community “Indoor Arabs”, an ignored people who have been raised to be quiet.

Muhammad knows the southern kibbutz community very well. He designed many of the country clubs, leisure centres and swimming pools in the kibbutzim dotted along the Gaza boundary. He says: “Ziv spoke Arabic. When the attack happened, I was hoping that my young friend would tell his assailants in Arabic that all his life he fought for Palestinian steadfastness.”

The bitter irony of the victims, hostages and survivors of the attack is that a large number of them had been actively working as pro-Palestinian activists; many were members of the peace movement, including Rabbis for Human Rights and B’Tselem.

“It may shock you,” Muhammad says, “but I wasn’t surprised – an attack was just a matter of time. We’ve been seeing rising tension between the communities since the May 2021 Gaza war, but I never expected the extent to which the atrocities were carried out.”

“Perhaps it’s the details of the massacre that left the country in shock, rather than the numbers?” I ask.

“You may say so. But why do details matter? If Hamas had the capability to push a button and kill 4,000 Israelis [the reported number killed in Israel’s bombing campaign in Gaza at the time], they would have done it. The group didn’t have that capability. Is there such a thing as dignified killing? Killing is killing. If one is shot in the head and dies immediately, does it make it OK?”

Rayek in his coffee shop in Neve Shalom

As I continue my journey meeting the troubled peoples of a land fraught with uncertainty, I’m joined by Ezekiel (not his real name), a former soldier who fought in one of Israel’s last wars with an Arab neighbour. He tells me that in some cases on 7 October the Israeli army did not arrive until 30 long hours after the attack was reported.

He drives us along the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv Highway 1. He swerves and takes the exit at Latrun junction. We start a gentle climb. The slanted October sun bathes the hedgerow and roadside cacti in a kind of primordial beauty. The domes of a monastery are slowly coming into focus. It seems odd we’re talking about a massacre when the land is at its most biblically elegant.

Ours is the only car on the road that leads to the monastery. Ezekiel narrates insouciantly the details – some already in public knowledge – of how the gunmen wanted to take the headquarters of the IDF’s Gaza division (near the music festival that was attacked), which they did and kidnapped twenty women soldiers.

“When they arrived in Re’im, the ravers were fairly tripped out on psychedelics. The video footage appears as if we’re watching a zombie film, you see hundreds of young people running towards their cars parked along the main road to escape… they were not in a fit state to run, and then they’re gunned down. Their bodies collapse on their parked cars, in the field, on the arid ground.”

“The attack on the music festival happened at around 10am – three hours after the gunmen entered,” says Ezekiel.

I hear that by this time, through holes in the fence, thousands of Gazan civilians – men and women – poured into the kibbutz nearest to the boundary. They’re caught on camera, seen to be looting. In one puzzling piece of footage, there’s a pregnant Gazan woman wandering among the gardens of one of the kibbutzim; another person appears to be taking a children’s bike.

The crisis we’re in depicts our feeling of abandonment… the decimation of the state

“By this time their ‘victory’ is being celebrated inside Gaza, and elsewhere among Palestinian refugees – this was the first-ever Palestinian retaliation for Nakba [the forced expulsion of Palestinians in 1948].”

A child’s sketch of the situation

I try to make sense of what Ezekiel has just said. Palestinian retaliation for the day of catastrophe in 1948. As if to address my racing thoughts, he points to the lush surroundings. The land here is bordered with rows of ancient cacti. That was the clue. There had once been a settlement. “Don’t underestimate the power of the Nakba memories,” he murmurs.

There are subliminal signs of the uprooting of Palestinians in our immediate proximity. Beit Nouba, Yalo, Emmaus – the non-appearance of the three historic villages is alluded to by the well-established cacti fence. These Latrun villages were annexed by Jordan after the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, and thousands of Palestinian refugees arrived here from surrounding areas. But after Israel retook the villages in the Six Day War of 1967, they were destroyed by the IDF and their inhabitants expelled.

We silently drive to the gate of the monastery. It seems sacrilegious, amid historical and current realities of expulsion and massacre, when we decide to buy a bottle of Latrun wine and sit in the shade to hear the church bells. A strange calm envelops us.

After a north-south drive, I arrive back at Yael’s place in Jaffa. It is a secluded block of flats with a playground in the middle, which is eerily empty. Yael is out, so I wait on a bench in the children-less playground and try to imagine a normal time, pre-7 October…

“The question for me is, what does the southern massacre do to activists like me?” Yael says. “All my life I’ve been an activist, now this. We’re finding it hard, there’s a crack in society, and between us here and the international Left – who want us to denounce the terrible tragedy Israel has been inflicting on Gaza, before we could mourn for our own dead. Why should condemning what happened in the south two weeks ago be seen as condoning the occupation?”

There is a sense of exhaustion, resignation in her voice. “What is scary is that securing the return of our hostages doesn’t seem to be the priority of the government.”

We’ve been seeing rising tension between the communities since the May 2021 Gaza war

After the massacre of the festival-goers, a massive X/Twitter exchange followed, with many, both in Israel and abroad, posting comments over photos of young people dancing, including “Who hosts a Rave Party next to World’s largest Concentration Camp and one of the disputed borders in the World?”

I reflect on another thought that involves some people enjoying normal life while others nearby are suffering. I used to live in Jerusalem’s Musrara neighbourhood, near the Russian Compound, also known as Moscobiyeh, a former British Mandate prison where detainees from the West Bank and Gaza are interrogated. My house was barely ten metres from where young and old Palestinians languished in cells without a trial in sight, while I took the children to school, walking across the prison car park. I spent many evenings in bars and restaurants on adjacent Prophets Street and Jaffa Road. In a war society, such juxtapositions are commonplace.

Yael says her country has arrived at a South Africa moment. “But the problem is that Israelis are not going to acknowledge it.”

And even if they want to, they’re not allowed to. Protest against the Israeli offensive in Gaza is prohibited. I join Yael and other activists on a Saturday evening – two weeks after the 7 October massacre – at a demonstration organised by victims’ families. It is on Kaplan Street in Tel Aviv, the site of ten months of pro-democracy protest against the government’s controversial, judicial overhaul plan. The street now resounds with a different kind of protest, on a sadder, much smaller scale. Wearing yellow ribbons, people who are holding banners saying “Prisoner Exchange Now!”, “Ceasefire, Bring ’em Back” cannot say openly, for example, “Stop bombing civilians in Gaza”.

Yael says: “I am happy to see the families chose this place. Which is not surprising, because they were supporters of the movement. People who were protesting in Kaplan against the government were trying to prevent a disaster that everyone thought was imminent, but here comes the disaster unexpectedly from somewhere that no one was prepared for. It’s an epic crisis.”

Everyone I speak to expresses a sense of abandonment in the deepest kind of way at the recurring question: why did nobody come? The families of hostages and victims are calling for Netanyahu to answer why the government failed to protect its citizens.

Latrun monastery leased a large chunk of land to Bruno Hussar, an Egyptian-French Jew who converted to Christianity and arrived here in 1953. A self-professed man of four identities – Jew, Christian, Israeli and Egyptian – he wanted to build an intentional community of Arabs and Jews. The result of his conviction is today’s Neve Shalom, or Wahat al Salam, Oasis of Peace, that sits among a conjoined range of hillocks overlooking the monastery. Since 7 October, a sense of terror has taken root among the residents of the scenic village – the only place in the whole region where Jews, Christians and Muslims live together.

“By choice,” Rayek Rizek tells me, in the village’s only coffee shop and meeting point which he runs. But his café is empty. I spend the whole day talking to him about his seminal book on the formation of this remarkable community, The Anteater and the Jaguar, during which just a few children come to buy ice cream, and a photographer asks for direction to the village’s multi-faith prayer room, the Dome of Silence. Rayek tells me that the inter-communal trust between Jews and Palestinians is being tested to its utmost limits. Neither side trusts the other.

Later, I sit in the living room of a Persian Jewish inhabitant of the village, Ruti, who was born in the central Iranian city of Abadan in the 1950s, with her husband, Hezzi, the son of Romanian Holocaust survivors, and Samah Salamei, a Palestinian peace negotiator. Also in the room are Ruti and Hezzi’s children, Noam Shuster Eliassi, a well-known left-wing comedian, Omer, a convert to Islam, Omer’s observant Jewish wife, Roni, and Ruti and Hezzi’s grandchildren, four-year-old Dalia and baby Nur-ed-Din. Dalia speaks Arabic to her father, Hebrew to her mother.

We need a new social contract about what a state is and how it is going to protect its citizens

Bruno’s multiple identities could not have been more successfully passed on than to his community in Neve Shalom/Wahat al Salam. But my outsider’s fantasy is broken by what Samah Salamei says next: that the village’s communal harmony is at a breaking point. She tells me that 50 per cent of the villagers have relatives in Gaza. Many of them have lost loved ones in Israel’s bombing campaign.

“Our village was born 42 years ago. Never before have we seen such a crisis of mistrust and mutual suspicion,” she says. Her face is barely able to contain her helplessness. She has lived here 23 years and works for the two sides to accept each other’s narratives and come to a common objective.

Gaza is an hour’s drive away from the village. From the terrace of Ruti and Hezzi’s house, the distant skyscrapers of Tel Aviv can be seen shimmering like a mirage. No place is safe, the residents tell me, the village has chosen mediators who are speaking to the Jews and the Palestinians separately. The parties are not brought directly to the negotiating table – to stop each of them from shouting out who has been more wronged.

With warplanes roaring overhead and amid sounds of sirens, I hear from the village’s Palestinians whose relatives were killed in Gaza, while a distraught Noam tells me she had been to a number of shivas – Jewish mourning periods – including one where Jews, Muslims and Christians all joined to pay tribute to a Jewish activist who was killed by Hamas gunmen on 7 October.

The tension is palpable, but everyone is trying to hold onto the village’s founding principle: “sharing lives” – acting together to bring about an end to mistrust. While the streets of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv are quiet, soulless, there is a cacophony of Hebrew and Arabic voices in the streets here as the children of the village play near Bruno Hussar’s specially designed multi-faith prayer room – the majestic white Dome of Silence.

Deserted flea market, Jaffa

Back in Jaffa, sitting in the only café that is open in the flea market, I see around me the painful desolation and silence of a society at war. Yael says 7 October is a clear warning – of what can happen to a society that “embraces neo-liberalism, that allows the kind of racial differentiation, differentiation between populations, that we had. It definitely offers the world a case study to see what not to do.”

She says: “It’s a dramatic moment. We need a new social contract, which is about what a state is and how it is going to protect its citizens and what citizenship means for all. We have to remember that there’s a difference between Palestinian and Jewish citizens. Being Palestinian means you’re not protected, but being Jewish didn’t always mean that.”

Muhammad and Noam, the comedian, who lives in Jaffa, join in to say that Hamas, as a fundamentalist organisation, suits Israel in not wanting to reach an agreement with the Palestinians. Muhammad tells me that the government historically upheld Hamas over the Palestinian Authority, giving it money, access, creating arrangements such as permits for workers – “The idea was you keep Hamas financially happy to keep dangerous dissatisfaction at bay.”

Noam says: “The government told us what keeps security in society, was an assortment of restrictions: the wall, the permit regime and surveillance.”

But the truth, the residents of the mixed city of Jaffa tell me, is that their country is experiencing a colossal tragedy of errors. The two peoples are on the verge of an eternal set of retaliations and vengeance. If the government thinks it can take over Gaza and destroy all the tunnels until the last Hamas member is dead, the residents of the kibbutzim will still not be able to return there unless Gaza as they know it changes significantly.

Ezekiel, the former soldier, and I embark on another drive toward the south. I ask him how a new Gaza can be achieved. He replies that the logical thing will be to have a package deal, comprised of four components: “All 5,000 Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails to be released in exchange for 215 Israeli hostages in Gaza; Israel and the international community to promise to facilitate a new Gaza that’ll be open to the world; total reconstruction with heavy investment, including from the Gulf countries; and lastly, demilitarisation.”

He acknowledges that it is a cliché that every crisis is an opportunity but says that if Israel can say to the Palestinians that the endgame of the war with Hamas will be these four components, there is a glimmer of hope.

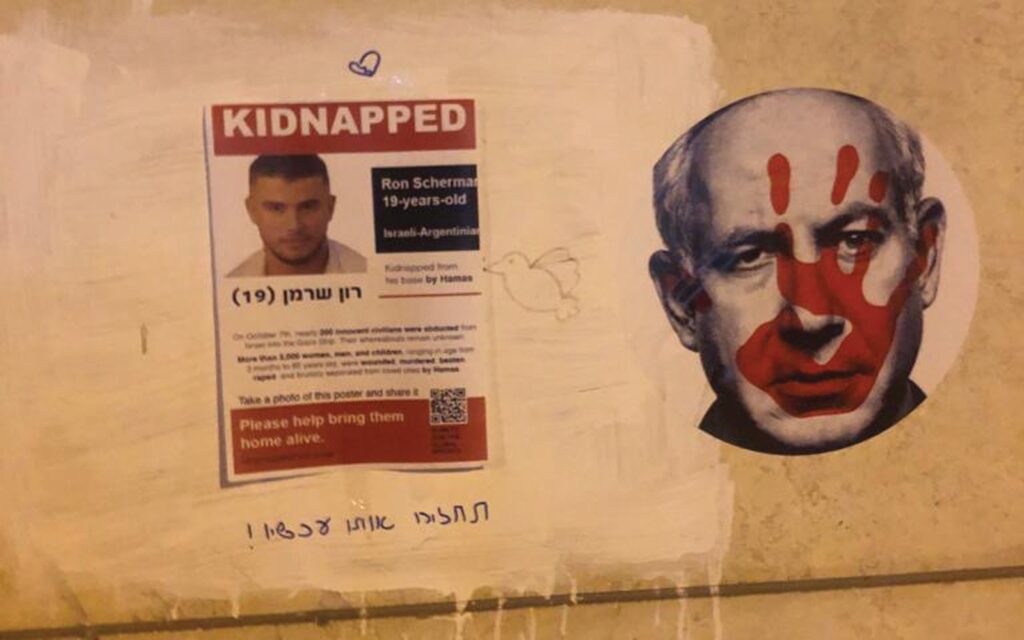

A poster of a kidnapped victim alongside and anti-Netanyahu sticker

My journey to the south is cut short in the town of Beer Sheva. I had been asked to go there and wait for Yakim, a young reservist – one of more than 350,000 called up to join the force for a ground offensive. I wanted to find out what the morale was among those preparing to fight an invisible army that has an intricate network of tunnel under northern Gaza.

He has sent me a series of cryptic WhatsApp messages over the past week: “They recruited me. I am now in an army basis in the south. You are welcome to come here.” Then: “You can meet me at 16:00 at Beer Sheva”, followed by a long silence. Meanwhile the news has been full of speculation about an imminent ground operation. When I contact him again to meet, he sends this message: “I can’t go out of the base today.” I say I can wait around for him. But he replies: “We have a lot of arrangements. We don’t have much free time. We have some special practice.”

Yakim has never been a fighter-type. When I ask if he had a choice to decline the emergency call-up for the ground offensive, he gets angry. He sends a voice message saying he does not know what kind of step the Israeli government can take except to totally eliminate Hamas – they are exactly like ISIS.

When I put that to Ezekiel, he says that it is crucial this operation will not be only a military one. It is possible to conquer street by street, but without a plan there will only be more bloodshed. “You can take Hamas out of Gaza, but you can’t uproot the idea of Hamas from the hearts of its people.”

Lipika Pelham is a historian, journalist, documentary filmmaker and the author of Passing: An Alternative History of Identity; Jerusalem on the Amstel: The Quest for Zion in the Dutch Republic; Conversations Across Place, and The Unlikely Settler. She has recently completed a PhD commentary on Sephardi Jewish converts in Early Modern Amsterdam: The Quest for Zion In The Dutch Republic, at Westminster University, London. Lipika currently works on the news desk at BBC News Online, and BBC World Service, covering primarily Mideast news. She is also a globe-trotting Special Reporter for London-based Perspective magazine.