Amat al-Latif enjoyed a privileged childhood in a high-ranking family at the heart of Yemeni politics; yet the failed revolt of 1948 was the family’s downfall, leaving her and other relatives exposed to the indignities of destitution. Through one family’s story, the book explores how political violence translates into tragedy in the personal realm, and how individual lives and larger cultural and political worlds intersect. Amat al-Latif’s narrative draws attention to experiential dimensions that were either not known, or deemed insignificant by most male historians. It throws light on the effect violent conflict has on kinship relations and on the lives of the survivors who had been entitled and accustomed to men’s provision and protection, and shows how women were bearing up faced with violent bereavement and psychological injury.

Amat al-Latif wanted her vulnerability to be acknowledged and to testify to her tribulations rather than to undertake a rigorous analysis of the events of 1948. The book seeks to illuminate how she positions herself in history, and to document the inescapable aftermath of these tribulations. Even while it has not been Amat al-Latif’s objective to explain her relatives’ aspirations and actions in a systematic way, her reminiscences reveal the impact politics had upon them. They demonstrate that her historical consciousness is shaped by kinship relations.

“Amat al-Latif’s narrative draws

attention to experiential dimensions that were either not known, or deemed insignificant by most male historians.”

In her narrative, ‘political events’ are embedded in and interwoven with other momentous ones that have impacted upon her life’s trajectories: the loss of loved ones to disease and execution, early marriage and dispossession after the failed revolt, as well as conflicts with her husband’s stepmother. Her story is thus uniquely personal and political at once. Part of her story centres on the aftershock of her father’s and young husband’s execution, and the ways she constructs her subjectivity around this grievous loss. Contracting another marriage in the following years, she moved abroad with her new husband, only to be caught up in armed conflict and renewed flight once again. After agonising soul-searching, she came to terms with her husband’s second marriage, which she considers another tragedy of her mature years. Her narrative negotiates the disparities between men’s and women’s ethical reasoning and practice, and offers insights into the gender dynamic of multiple simultaneous marriages.

The book draws attention to Amat al-Latif’s memory work. Instead of pursuing a chronological order, it creates links between tropes that take centre stage in the narrative and conspicuously reappear in a number of contexts. For example, her memory moves from joyful childhood days to devastating events in her adult life with great ease. Talking about the intimacy that characterised the relationship with her father, she immediately turns to his arrest, thus amplifying the intensity of her distress and sense of loss. The constant movement from and fusion of the intimate and the political and the association of events that were experienced in entirely different contexts and time frames are both characteristic features of her narrative. Her cycling between catastrophe and hope was occasionally signalled by a switch from the past to the present tense, giving the impression that the present is composed of several layered and intertwined temporalities. Frequent repetitions constitute a narrative pursuit in its own right, reflecting her concern to highlight the injustice done to her father and his dependants. They provide further emotional poignancy to the story, and is to be read as part of the process of recollection, as are the elisions, silences, confusions and moments of forgetting.

“Her narrative negotiates the disparities between men’s and women’s ethical reasoning and practice, and offers insights into the gender dynamic of multiple simultaneous marriages.”

Though written at the level of gendered subjectivity, Amat al-Latif’s story is told through an intersubjective lens centred on her relationship with her father. She unwittingly detaches herself from the common autobiographical fixation on the autonomous subject. As a daughter who seeks to exonerate her father, she lays claim to an authority that rests in the morally charged, embodied acts of intimate being-with, of bearing witness to his morally impeccable conduct. She emphasises his selfless sacrifice for the nation and insists that allegations regarding his involvement in his predecessor’s assassination were belied by his devoutness and disapproval of violent overthrow.

.

.

.

.

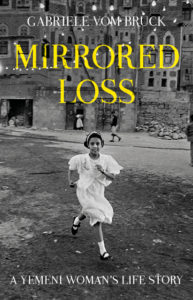

Mirrored Loss: A Yemeni Woman’s Life Story by Gabriele vom Bruck