Earlier this month, an FIR, or preliminary Indian police report, was registered against Tushar Gandhi—great-grandson of the Mahatma—following comments he allegedly made when weighing in on an old debate about whether Gandhi had done enough to save the young revolutionary Bhagat Singh as he sat on death row, in 1931. Tushar Gandhi is reported to have said that Bhagat Singh was a ‘criminal’ in British eyes, and as such, ‘Mahatma Gandhi had not asked for suspension of his sentence’ (Times of India, May 11, 2015). The case has been registered under Section 295 (A) of the Indian Penal Code, which provides for the prosecution of ‘deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings’. Calls have been made for Tushar Gandhi’s immediate arrest, while others have asked how his comments amount to a specifically religious insult. Such is the following that Bhagat Singh now commands, that his revolutionary nationalism has attained a quasi-religious sanctity.

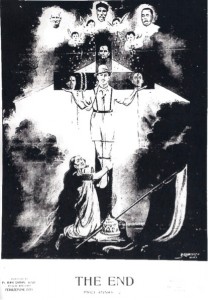

Interestingly, a variation of this trend was discernible back in 1931, when artists frequently portrayed Bhagat Singh by deploying religious themes. He was variously depicted as a martyr in heaven, in the company of celestials or divinities, and even as a crucified Jesus Christ. This particular representation of Bhagat Singh astounded British onlookers, not only for its appropriation of Christian imagery, but because it was so prominently displayed in public spaces (despite being formally banned as ‘seditious’). This was indicative of a new spirit of rebelliousness that Bhagat Singh popularised and indeed epitomised. This, and the corresponding fear that it instilled in Britons resident in India at the time, was just one of his legacies to the Indian freedom struggle.

In A Revolutionary History of Interwar India, I noted—as so many others have before me—that despite his epic popularity Bhagat Singh’s life and death have yet to be incorporated into scholarly accounts of mainstream nationalism. Instead, revolutionary stories have been largely peripheral to the story of the Congress-led nationalist movement in India. At best, Bhagat Singh is mentioned only in passing, in the context of the Gandhi-Irwin talks in February 1931, following the first round of Civil Disobedience. At this juncture historians invariably note that Gandhi did not make the commutation of the death sentences on Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru a condition of the agreement (it was this event that Tushar Gandhi sought to explain when he used the word ‘criminal’ to describe the revolutionaries).

I argued in my book that in order to understand the praxis and the impact of Bhagat Singh’s party on the politics of the interwar period, we needed to transcend the colonial government archive. There are innumerable files on the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army (HSRA) held in various collections in India and the UK, all written with the purpose of investigation, prosecution and punishment. Yet the language of condemnation in which these documents are crafted reveals more about the British than about the revolutionaries. Loaded terms that British investigators used—‘criminal’, ‘terrorist’ and ‘murderer’, for example—functioned simply to excise political violence from the circle of reason and justifiability, rather than to understand what was an important and rising phenomenon. If we are to uncritically borrow that language, as Tushar Gandhi does, we risk imbibing the sensibilities embedded therein.

To provide just one example: after his arrest, following the bombing of the Legislative Assembly on 8 April, 1929, Bhagat Singh was asked by British investigators why he had not taken the opportunity to shoot Sir John Simon, the leader of the much-despised parliamentary commission, who was present in the chamber at the time. Bhagat Singh responded that the HSRA had indeed considered doing so, but decided against it because the revolutionaries ‘feared that if the shot missed Sir John it would kill the brother of Mr [Vithalbhai] Patel’, who was seated next to Simon. This truly confounded the investigators; Bhagat Singh’s scruples challenged their understandings of the revolutionary as unilaterally dangerous. They therefore dismissed the comment as ‘abnormal’. Unfortunately for the British, this blinded them to an important phenomenon—of the active synergies and clandestine collaborations that existed between prominent Congress leaders and revolutionary activists. Needless to say, this did not include Gandhi.

These are secret histories, and the task of telling secret histories demands innovative methodologies. By carefully reading colonial documents against other forms of evidence—oral history interviews, revolutionary memoirs, popular imagery and rumours—I demonstrated in my book that the HSRA invited the Congress to capitalise on its ‘actions’, as they called their carefully orchestrated acts of political violence. While it was emphatically not their primary goal, the revolutionaries realised that their politics created the conditions in which the British were more likely to initiate constitutional reforms, in at least some sort of dialogue with the Congress. As Motilal Nehru demanded of the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, in his pithy response to the bombing of the Legislative Assembly: ‘Gandhi or Balraj?’

Without Balraj—a revolutionary pseudonym that also translates as ‘the rule of force’ – there was relatively little impetus for Irwin to negotiate with Gandhi (in the process so antagonising Winston Churchill, who was infamously ‘nauseated’ to see Gandhi ‘parley on equal terms’ with the Viceroy). The political outcomes of these parleys were disappointing to many, including the revolutionaries, as is clear from Bhagat Singh’s last writings from prison. But Bhagat Singh never wanted or expected commutation, indeed he welcomed his death, understanding full well the political potency of his martyrdom.

Kama Maclean is Professor of South Asian and World History, at UNSW Sydney, Australia, and author of A Revolutionary History of Interwar India: Violence, Image, Voice and Text.