To explain the unnerving and unstoppable march of capitalism in the mid-20th century, Joseph Schumpeter coined the term ‘creative destruction.’ The engine of capitalism was fuelled by a voracious impulse to devour yesterday’s commodities and thus clear the way for new products for the insatiable appetite of the consumer to feed on.

To explain the unnerving and unstoppable march of capitalism in the mid-20th century, Joseph Schumpeter coined the term ‘creative destruction.’ The engine of capitalism was fuelled by a voracious impulse to devour yesterday’s commodities and thus clear the way for new products for the insatiable appetite of the consumer to feed on.

In India, ‘creative destruction’ once referred to the cosmological realm occupied by the King of Dancers, Shiva-Nataraj, whose continuous dance of creation and destruction governs the universe. In Nehru’s newly independent India, the idea of inducing consumption for the sake of updating to the newest model was almost sacrilege. During the first few decades of independence, material pursuits were frowned upon, while progress and industrialisation were founded on ideals of self-sufficiency and self-reliance.

In India, ‘creative destruction’ once referred to the cosmological realm occupied by the King of Dancers, Shiva-Nataraj, whose continuous dance of creation and destruction governs the universe. In Nehru’s newly independent India, the idea of inducing consumption for the sake of updating to the newest model was almost sacrilege. During the first few decades of independence, material pursuits were frowned upon, while progress and industrialisation were founded on ideals of self-sufficiency and self-reliance.

While India was championing a controlled economy and five-year development plans, across the black waters (kala pani) the US fell under the sway of a different kind of planning—planned obsolescence, in which goods were intended to have a limited life and become obsolete, for reasons either of technology or fashion.

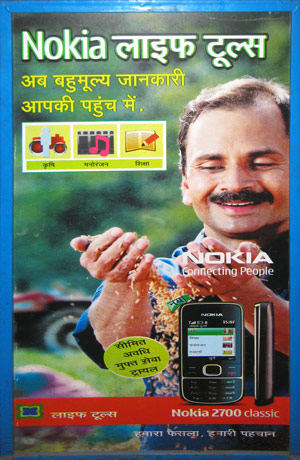

Fast-forward to the 21st century and India’s policy of neo-liberalism captures headlines with its accelerating economy, booming consumerism and a middle-class yearning for full participation in the global economy. This is an India where the throwaway ethic is taking root and Gandhian ideals of self-reliance are increasingly obsolete. This is an India where the single largest category of consumer goods is the mobile phone.

With over 900 million mobile phone subscribers, India’s decennial census in 2011 revealed what many found remarkable. The country had more mobile phones than it had toilets. But a closer look at the mobile phone and its many lives reveals a different story. That story, which is different from the capitalist version of ‘creative destruction,’ remains in tune with the old ethic of durability and is embodied in India’s tens of thousands of second-hand dealers and craftsmen.

With over 900 million mobile phone subscribers, India’s decennial census in 2011 revealed what many found remarkable. The country had more mobile phones than it had toilets. But a closer look at the mobile phone and its many lives reveals a different story. That story, which is different from the capitalist version of ‘creative destruction,’ remains in tune with the old ethic of durability and is embodied in India’s tens of thousands of second-hand dealers and craftsmen.

The existence of a vast market for repairing durable objects, especially mobile phones, remains puzzling for many. How do we explain the persistence of non-conventional, illicit consumer behaviour that defies normative global practices of consumption and disposal? Isn’t there supposed to be a risk-calculating behaviour embedded in consumer capitalism which leads consumers to reduce risk by assigning it to certified individuals representing great brands that offer guarantees and warranties?

But India’s population of more than 900 million mobile phone users relies little on product warranties. Rather, informal service providers systematically breach copyright laws to replace and refurbish handsets with unauthorised components and software.¹ How do we account for modes of consumption that court risk rather than avoid it? Such questions tax us as we marvel at the story of the mobile phone in India and the insights it offers into India’s brand of consumer capitalism.

NOTES

¹ Doron, A. (2012),’Consumption, Technology and Adaptation: Care and Repair Economies of Mobile Phones in North India’, Pacific Affairs, Vol. 85, No. 3.

(Photographs: © Assa Doron / Robin Jeffrey)