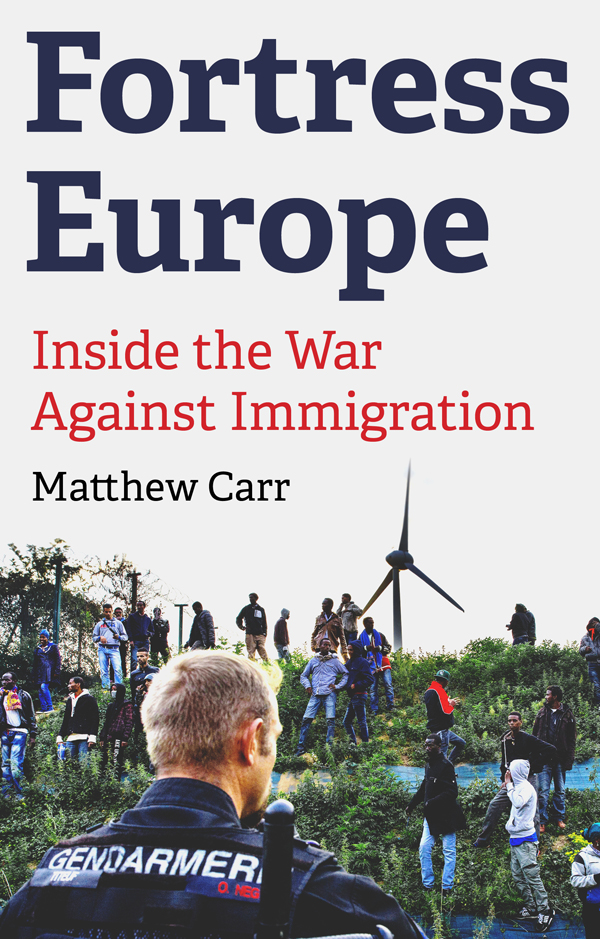

Think of borders in the twenty-first century and you immediately think of walls, barbed wire fences, razor wire, checkpoints, quasi-military border patrols on land and sea, surveillance cameras, sensors and a panoply of high-tech paraphernalia whose essential purpose is to keep unwanted people out. This is the kind of imagery that we tend — rightly — to associate with ‘Fortress Europe’ and other border regimes that have begun to proliferate across the world, and on the Western borders in particular.

These reinforced barriers, we are told, are intended to protect us from Islamic State and other enemies that want to kill us; or from other morbid consequences of the ‘dark side of globalisation’ such as human traffickers, drugs, organized crime or sexual exploitation. We take it for granted that such barriers are necessary to protect our labour markets, our welfare systems, our cultures and our lifestyles against unwanted ‘illegal immigrants’, whether they come in the form of despised ‘economic migrants’ or ‘bogus asylum seekers’ or simply refugees who we don’t want to find room for.

Governments routinely attempt to draw political capital by demonstrating their ability to exclude unwanted ‘illegal’ people at the border and deport those who make it through these barriers. The European Union has attempted — with catastrophic consequences — to ‘manage’ and control the new twenty-first century migratory movements that are generally deemed to be harmful and threatening.

But there is also another dimension to the ‘Fortress’ model which tends to receive less attention; namely that these barriers are not impermeable, and are not even intended to be. Every year tens of thousands of ‘illegal immigrants’ succeed in crossing Europe’s borders, and some of them succeed in finding work. Usually they jobs they do are unskilled, low-paid and off the books. They might work in construction, fruit-picking, agriculture, food production, or cockle-picking. They might be found in the rural economies of peripheral European countries such as Greece, Spain or Italy, in Morecombe Bay, Madrid, Brescia or Athens.

These are the workers who inhabit the Sheffield of Sanjeev Sahota’s powerful novel The Year of the Runaways; men and women without rights, who can expect no holidays, no sickness or unemployment benefits, and no pensions. Legally they don’t exist, but their illegality means that they are constantly visible to police and immigration officials, and liable to immigration raids, detention and deportation.

This is the grim reality for hundreds of thousands of men and women across Europe, who illegality makes it possible for them to work and yet also traps them in a permanent legal limbo where they can never access the rights of the ‘legal’ indigenous workforce, let alone the rights of national citizens.

Governments occasionally acknowledge this phenomenon, and shake their heads or wring their hands about it. Some countries issue periodic amnesties which allow illegal workers to step out of their invisibility; others promise to crack down on the gangmasters and employers who make use of such labour — even if these efforts tend to be half-hearted and generally driven by the desire to deport undocumented migrants rather than protect workers from exploitation.

This new flexible ‘reserve army of labour’ is not simply an accidental consequence of Europe’s ‘hard’ borders, however. When I was researching my book Fortress Europe, I met African workers in the greenhouses of Almeria in southern Spain who lived in shacks and were paid well below the minimum wage; and workers in the city of Brescia in northern Italy who staged a spectacular protest on a crane because they had been conned into paying for legal permits that they were never going to receive.

Nowadays, the indigenous European workforce is often encouraged to see migrant workers as competitors stealing ‘their’ jobs, but it was clear in these and in other cases, that the undocumented workers who made it through Europe’s lethal gauntlet were generally doing jobs that Europeans did not want to do, and that their illegality had left them stranded in a permanent zone of exploitation that they could not change or escape from.

This is the argument that the LSE criminologist Dr Leonidas Cheliotis has made in a compelling new paper ‘Punitive Inclusion: A Political Economy of Irregular Migration in the Margins of Europe’, which is due to be published in the European Journal of Criminology.

Basing his research mostly on his native Greece, Cheliotis argues that the lethal Greek borders that have claimed so many migrant lives in recent years are actually more permeable than they appear, and that as a result, ‘large flows of irregular immigration have effectively been channelled towards Greece’s perilous though still porous borders by ever-tightening restrictions imposed across Europe upon irregular immigration from other parts of the world, in the form, for example, of stricter policing of national borders and narrowed opportunities for accessing asylum and visa procedures.’

This combination has left nearly 400,000 undocumented migrants trapped inside Greece, on the desperate margins of a society in crisis, working in the largest shadow economy in Europe. Not only have the border controls established by the European Union and successive Greek governments failed to prevent the exploitation of the undocumented migrant workforce, but they have actually facilitated it, since:

‘The massive swathes of irregular migrants who keep crossing the porous Greek borders in search of a better future lend themselves ideally both as exploitable workers and amenable reserves. For one, their numbers help ensure that a sufficiently large pool of ‘surplus’ labourers is always at hand, whilst their desperate predicament as a result of poverty and attendant needs (e.g., to earn a living) further inclines them to exploitability if and when a job becomes available.’

The ‘exploitability’ of migrant workers in Greece, Cheliotis suggests, is facilitated by a dysfunctional and protracted asylum system and an inadequate and cumbersome regularisation process that generally issues only temporary work permits, when it issues them at all, and which has transformed migrant workers in emblematic members of the new twenty-first century precariat living ‘in limbo, shifting between regular and irregular status with long breaks filled with uncertainty and anxiety in between, when their chances of falling victim to unscrupulous lawyers, mafia operators and corrupt state officials are also greater.’

All this is bad enough, but migrant workers are also subject to racist attacks by Golden Dawn fascists and to ‘intimidatory practices of over-policing, including a greater likelihood of being stopped and searched, alongside so-called “sweep” or “cleaning operations” launched in the name of fighting illegal immigration and associated crimes.’

All these components are part of a process that Cheliotis calls ‘punitive inclusion’ in which:

‘apparently unrelated policies on matters of immigration, welfare, employment and punishment, together with practices of anti-migrant brutality and intimidation by state and non-state actors, have effectively formed a continuum of violence that forces irregular migrants either to submit to any available condition of work or to await for their chance in a disciplined fashion.’

The same could be said of many of the estimated four million undocumented workers in Europe. In his incisive analysis of the relationship between illegality and exploitation in Greece, Cheliotis has also drawn much-needed attention to a generally unacknowledged consequence of our world of proliferating borders.

Many of his conclusions can be applied not only to Fortress Europe, but to the US-Mexico border and other barriers across the world that seek to keep certain categories of ‘illegal’ people out, even as they ensure that others are trapped inside them, at the very bottom of the great pyramid of precarious ‘flexible’ labour that our unequal and grossly unjust world increasingly relies on.

For a copy of the paper, contact Joanna Bale, LSE Press Office, [email protected].

Matt Carr is a freelance journalist whose work has appeared in The Observer, The Guardian, The New York Times and on BBC Radio. He is the author of The Infernal Machine: An Alternative History of Terrorism; Blood and Faith: The Purging of Muslim Spain, 1492-1614 and most recently, Fortress Europe: Inside the War Against Immigration. His widely followed blog can be found at Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine

On Twitter: @MattCarr55