The oasis of Gaza—the last outpost before the Sinai desert—has for thousands of years been a strategic objective for conquerors of all kinds. Any Middle Eastern empire had to control Gaza in order to confront Egypt, and any campaign towards the Nile Valley had to be launched westward from Gaza. From Alexander the Great in 332 bc to the Ottomans in 1516, control of Gaza was a prerequisite for confronting Egypt.

Moreover, any power ruling Egypt had to control Gaza in order to break through Palestine and the wider Levant, which is why the Pharaohs, the Ptolemaic dynasty, the Mamluks and even Bonaparte in 1799 sent expeditions from Egypt to conquer Gaza, before marching north along the Mediterranean coast. The strategic road through Gaza was called ‘Horus’s Path’ by the Egyptians, ‘Via maris’ by the Romans and the ‘Sultan’s way’ by the Mamluks.

The First World War witnessed the last clash between two empires fighting for control of Gaza as part of the struggle for Palestine and the wider Middle East. The Ottomans concluded a secret alliance in August 1914 with Germany. Sultan Mehmed V had the formal status of Caliph, but was by then the creature of the Young Turks, who devised with Berlin a baroque version of ‘jihad made in Germany’: the Caliph would declare jihad against the French, British and Russian ‘infidels’, while German agents would disseminate this declaration in Arabic, Persian and Urdu, hoping to foment trouble in their adversaries’ colonies.

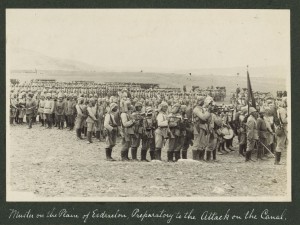

Berlin had nevertheless overestimated the prestige of the Ottoman Caliph among non-Turkish Muslims. ‘Jihad made in Germany’ proved a flop but London was in no mood for further strategic disturbance and imposed a fully-fledged protectorate over Egypt, after thirty-two years of British domination. The Jerusalem-based Jamal Pasha sent an Ottoman army through the Sinai down to the Suez Canal. It was defeated there in February 1915 and withdrew to the relative safety of Gaza, leaving only a few Ottoman outposts in the desert peninsula.

In March 1916 General Archibald Murray assembled an Egyptian expeditionary force that comprised significant Australian and New Zealand contingents. Nine months later, the British conquest of El-Arish completed the restoration of imperial rule over Sinai. A coastal railway was built to provision the Allied troops camping at the gates of Gaza, with water pipes running across the desert from the Canal. But Murray failed miserably in two frontal assaults on Gaza, in March and April 1917, suffering more than 10,000 losses (twice as many as were inflicted on its defenders).

Murray was replaced in June, following the Battle of Arras, by General Edmund Allenby. The new commander linked up with the Arab insurgents who had conquered Aqaba and were harassing Ottoman troops in the Negev desert. Allenby planned a coordinated assault on Gaza and Beersheba, the main oasis of the Negev. From 27-31 October, Gaza was pounded with artillery and ordinance from battleships and planes. Beersheba fell on 1 November and a week later the British army forced its way into Gaza.

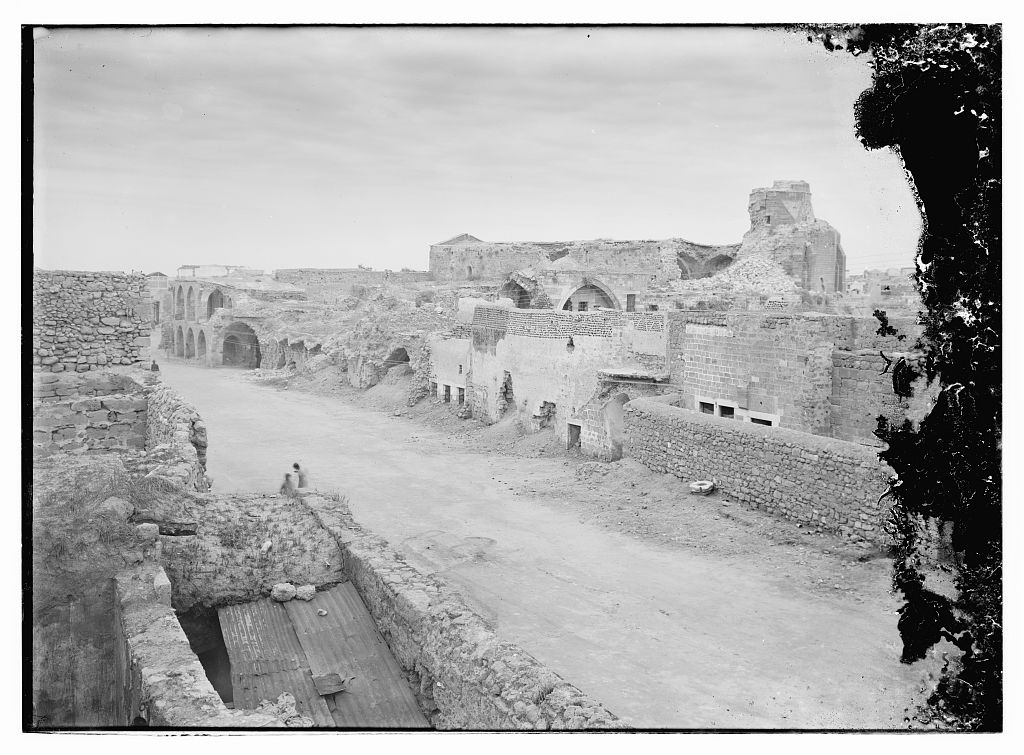

The city was devastated by British bombing, but also by the Ottoman practice of destroying local buildings in order to fortify their defences, and for many years after Gaza remained a depressing and ruined ghost city. Allenby entered Gaza on 9 November, the same day the British Foreign Office announced the ‘Balfour Declaration’ endorsed a week earlier: ‘His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment of a national home in Palestine for the Jewish people’. One battle for Palestine was over in Gaza, another was about to begin.

Jean-Pierre Filiu is Professor of Middle East Studies at Sciences Po in Paris and author of The Arab Revolution: Ten Lessons from the Democratic Uprising and, most recently, Gaza: A History.

Jean-Pierre Filiu is Professor of Middle East Studies at Sciences Po in Paris and author of The Arab Revolution: Ten Lessons from the Democratic Uprising and, most recently, Gaza: A History.

Click here to order Gaza: A History with a 20% discount and free international shipping.

More books on Israel and Palestine →