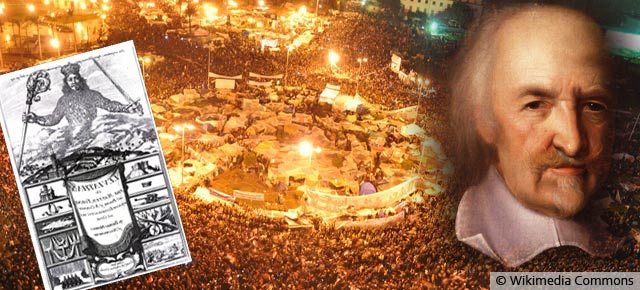

Hobbes might be taught in philosophy classes from secondary school onwards throughout the Western world, but he does not feature prominently enough in our understanding of politics today. Hobbes is said to have represented a stage in the development of Western thought, but also to have been superseded by more liberal thinkers, particularly Locke and Kant. Certainly, when we scrutinise Western European and North-American states, little seems to be left of the Leviathan: the rule of law reigns supreme and liberal institutions are rarely challenged. Until the end of the Cold War, it was understood, if hardly ever openly acknowledged, that even the liberal state might have to cooperate with and patronize old-style Leviathans in the unstable and underdeveloped lands of Africa, Asia and Latin America, as well as occasionally in Southern Europe. The supposed rationale for this was the major challenge presented by an even more dystopian Leviathan, the Soviet Union.

The end of the Cold War removed the need to support far-flung Leviathans, although this change occurred gradually and by 2011 it was still not complete. In many cases, Western policy-makers have waited hesitantly until revolutions have reached their most volatile stages before terminating their support for authoritarian governments, most recently in Egypt and Tunisia. Of the recently extinguished Leviathans many were both unable and unwilling to transform themselves into developmental polities and establish true political legitimacy, continuing instead to rely primarily on coercion to sustain their grip on power. However, the assumption that liberal states are always developmental, and that no other form of statehood can be developmental, is misplaced. Moreover one can hardly bring to mind even one example of a state that has ever been established other than as a Leviathan. A gradual evolution into more sophisticated forms of polities –– less and less reliant on coercion to control their populations –– sometimes then occurred, sometimes not.

This is not just an academic debate, as found in my new book, The Art of Coercion. When Western liberal states intervene abroad and seek to rebuild collapsed states, or to build new ones, they face the very same dilemma: how to combine the necessary recourse to coercion with liberal principles of how a state should be run. During the Cold War, Western governments invested in the building and consolidation of domestic liberal institutions (among others) for the purpose of building an ideological bulwark against ‘socialism,’ the ideology of the enemy. While this effort was a success, over the years it became so embedded in western identity that even policy makers, usually among the most cynical of human beings, had at least to pay lip service to this liberal ideology. Because the realities found in post-conflict or collapsed states are not conducive to the emergence of liberal institutions, Western policy-makers have been struggling to come up with strategies and policies that actually work on the ground.

In fact, even within the ministries of defence or foreign affairs of Western democracies, not to mention development ministries and departments, there is in most cases now a critical mass of officials who have been trained (indoctrinated, perhaps) to believe that the western contemporary model of the state can be replicated tout-court in post-conflict states. Once operating in those unfriendly environments, some of these officials rediscover their lost cynicism, but others do not.

The result is the characteristic two-tier policy pursued by Western state agencies when intervening in conflict and post-conflict environments: some agencies support institution-building, invest massively in it, advocate competitive and free elections, sponsor civil society organisations, even invent them when too few are readily available, always striving to create an environment that meets their ideological parameters. The western model of the state is predicated on a rich and assertive social environment, able to exercise oversight over state institutions. Hence the very strong drive to recreate that social environment, investing resources in the creation of Potemkin NGOs.

Other agencies, by contrast, sponsor state repression, or worse, rogue warlords and strongmen, unbound by rules and with a vested interest in opposing the consolidation of strong liberal institutions. Increasingly, the direct support for the agencies of state repression is politically unpalatable, has to be kept to a minimum, and must be accompanied by the imposition of strict rules on the behaviour of these agencies. The result is the tendency to rely on non-state armed groups (militias, warlords, strongmen and their retinues) to exercise what might be termed The Art of Coercion as far as is possible, away from the (western) public eye, and with as much ‘plausible deniability’ as they can.

While the practice has been widely criticised by human rights organisations because it is likely to lead to abuses, it has another major flaw, namely that it is not conductive to the consolidation of the Leviathan. As Machiavelli would have said, not all violence is the same, in that the dispersed coercion implemented by non-state mercenaries tends to be an end in itself. The historical experience shows that only the monopolisation of violence, and particularly large-scale violence, is conductive to the consolidation of the state in its most basic form, the Leviathan. Only the emerging Leviathan can monopolise violence.

Liberal critics are right to be fearful of the Leviathan: for if it is a necessary precondition for successful development, it is not an all-encompassing one. Moreover there is always the risk that the Leviathan may deploy its greater efficiency in managing violence to exclusively destructive ends. As serious civil society oversight of the security apparatus can only emerge once a society matures and prospers, the Leviathan can easily turn into a nightmare.

How does one tame the Leviathan before a civil society emerges? Again, not all authoritarian governments are the same. This is not an ethical statement, but a policy one: some authoritarian governments have been able to control their populations with little violence and were able to tame their security apparatus, even in the absence of a strong civil society. Perhaps something can be learned from their experiences, all the more so since liberal democracies do not seem to have the answer.